BookView Interview with Author Loretta Goldberg

Welcome to BookView Interview, a conversation series where BookView talks to authors.

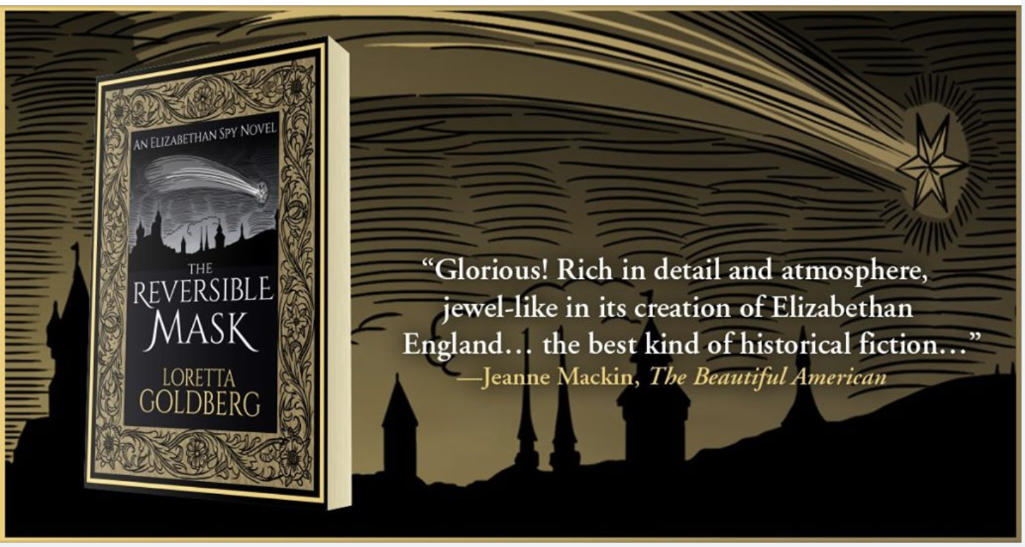

Recently, we interviewed Loretta Goldberg, the author of The Reversible Mask: An Elizabethan Spy Novel, a lush and inspiring historical tale. After careers in music then financial services, Loretta sold her financial services practice to focus on writing. (Read the reveiw here).

Tell us about how this story first came to be. Did it start with an image, a voice, a concept, a dilemma or something else?

A dilemma. I was in bed at night, reading. Suddenly I screeched “Oh no! Standen’s blown!” I had been doing a lot of non-fiction work on Elizabeth I. I came across a spy who provoked admiration, even affection, from some scholars but distaste from others. Intriguing. After centuries, consensus usually coheres about a person’s basic character. So I was chasing the spy in the papers of Anthony and Sir Francis Bacon, Elizabethan brothers and his spymasters. He was a handsome English expatriate double agent, cover now gone. At my screech my patient partner grunted, “Who cares?” That question began the novel.

Why did I care? Anthony Standen’s exploits were significant, but it was long ago. There were more compelling things to think about. Still, his predicament wouldn’t let me alone. His choices felt modern, urgent. My imagination filled in the sketchy dispatches in Bacon’s papers: he loved his Protestant birth country; he loved his Catholic faith. The imperatives tugging at him were irreconcilable. This was a time when people believed in a physical hell, when many went to the stake and were burned alive over defining the bread and wine in the Mass; were the bread and wine the body and blood of Christ (Catholic) or a symbol (Protestant)? A monk’s life wasn’t for this spy. He seemed to want to make his world better. He used his spying, and the resulting access to advisers to Protestant Elizabeth I of England and Catholic Philip II of Spain, to excoriate them for extremism. Brazen.

Modern life is full of compromises. At Gap I see the perfect shirt. Maybe a Bangladeshi girl stitched it. Maybe she died in a factory collapse. I buy the shirt. Nor do I do all I can to lower my carbon footprint, an existential issue. I try decently and compartmentalize. My spy COULDN’T compartmentalize. Here was the Platonic form of conflict, contained in one body for years. What did it feel like? Act by act, lover by lover? I fictionalized Standen to Edward Latham, peopled his society and thrust him at the era’s pivotal events.

Are any of your characters based on real people you know?

All of them, but not intentionally. Everything comes down to self-awareness and a capacity for empathy. I did years of research for The Reversible Mask. I loved and dreamed its characters. But ultimately, they’re bits of me and folks I’ve met. They can feel and do as much as I can imagine, not more.

Which scene or chapter in the book is your favorite? Why?

I like the Constantinople scenes, the dreadful comet of 1578 oppressing the sky for weeks. Edward is there, ferreting out secret negotiations between the Ottoman Sultan and European rulers. He is shocked to his core by the relative religioustolerance there. He meets the love of his life, an Ottoman slave named Ibrahim, converted from Christianity to Islam as a child. Edward’s jagged journey to maturity begins here. I play with the metaphor of many clocks telling different times to signify, for Ibrahim, that religious doctrines are as imperfect. I made a fun video of the clock scene at https://www.amazon.com/LorettaGoldberg/e/B07KBB72TX?ref_=dbs_p_ebk_r00_abau_000000

If you had to do something differently as a child or teenager to become a better writer as an adult, what would you do?

I would have worked as a reporter, rather than writing arts reviews for local papers. Reporters tell dramatic tales with few words, a great skill for an aspiring novelist.

Would you rather read a book or watch television?

Confession. I watch a lot of television. I like the words/images mix. That’s why I made videos for my author talks.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

The words “two days.” My Australian ex-husband arranged for us to marry in Jerusalem. He had two Israeli friends from his college days at Syracuse University, New York, Joshua and Aaron. They got things started. However, they didn’t coach me for my interview with the Sanhedrin, the Jewish religious court that would give final approval. They said, “They’ll ask a few questions. Just answer them”

I am by myself in a rectangular room with a tired grey wooden floor and dusty windows. I’m looking up at three bearded elders on a dais. The room is heavy with frowns, not smiles. They worry that my Rabbi’s letter from Melbourne, Australia, certifying me as Jewish isn’t enough. They need a second confirmation from thelocal Israeli who’d stated he’d known me for years.

You see what’s coming. Joshua had given that statement. It was true of my fiancé but not of me. But no one warned me. Did they assume I knew more than I did? The beards ask “How long have you know Joshua G?” Eyes raised, I default to truth. “Two days!” Fury. A lot of muttering between them, notes made.

I am confused. “Interpreter,” I plead. I ask to consult Aaron, the other college friend, waiting outside.

Aaron had been Irgun, a guerrilla fighter. Scholars didn’t scare him. He’s worried but not fazed. The beards demand that Joshua testifies immediately about the discrepancy. But he’s teaching in Haifa. Aaron tells the beards to wait while he goes to Haifa to get Joshua. This would extend the hours to the Sabbath. “No.” Aaron offers his wife. “If women get involved,” the beards growl, “there must be two women to equal the testimony of a man. You know that.” Aaron then says he’ll go to Australia and bring back my Rabbi. Hands on the doorknob, he flings back, “Wait here, just three days!” I see one slightly upturned lip on one of the beards. The Rabbis want to go home. My Rabbi’s letter has always been adequate.

Why did “Two days” represent the power of language? Lying to the Sanhedrin is a punishable crime. My “two days” could have got Joshua five years of hard labor if he’d been in Jerusalem that morning instead of Haifa. It equally represents the power of what words hadn’t been said to prepare me for the questions.

What does literary success look like to you?

Finding a publisher was a marvellous affirmation. But literary success for me is when a reader says it changed them, or that they need the sequel, they’re so into the characters. It has happened a few times, a fantastic feeling.

Does writing energize or exhaust you?

It energizes me. Even rewriting, despite the frustrating of going over and over stuff. When colleagues say something doesn’t work, the rewrite usually gets me closer to what I meant to say in the first place but was too nose to screen to see the flaws. Oddly, I even feel sense of loss at the “finish” line. Of course, there never is a finish line, but at some point you throw it out into the world.

Do you think someone could be a writer if they don’t feel emotions strongly?

Great question. As a kid I learned in biology classes that irritability signifies life. An amoeba shrinks at touch, therefore it lives. I believe that wanting to write, compose music or paint begins with emotional need: love, longing, pain, anger. Irritability! That doesn’t mean that a novel’s characters must engage deeply with each other. Thrillers are often carried by action and dread. But the need for resolution, to get the world back on a viable axis, is as passionate as love stories in other genres.

Have you read anything that made you think differently about fiction?

I was educated in nineteenth-century novels, where an omniscient narrator pulls the reader through the characters’ adventures. It’s in my blood. But Thomas Kenneally’s The Daughters of Mars, was a revelation. An Australian, he based his tale on diaries written by nurses from rural Australia who nursed at the fronts of World War I. What’s astonishing is that you never know or feel more than the naive nurses do at any moment. No current understanding of that catastrophic carnage creeps into the narrative. I admire this discipline more than I can say, being a factoid addict myself!

What’s next for you?

A sequel to The Reversible Mask. There are irresistible ironic turns in Edward’s journey from his present triumph to setbacks and old age. I’m also working on a novel set in Papua New Guinea during World War II. Four cultures converge: the Australian ruling elite, woefully under-resourced for war; native Tolai serving them who are sophisticated and self-sufficient in their own way; an entrepreneurial Chinese community; and the Haiku-loving vicious Japanese invaders. A challenge that will keep me out of mischief!

www.lorettagoldberg.com; facebook.com/LorettaGoldbergAuthor; In; Loretta@lorettagoldberg.com