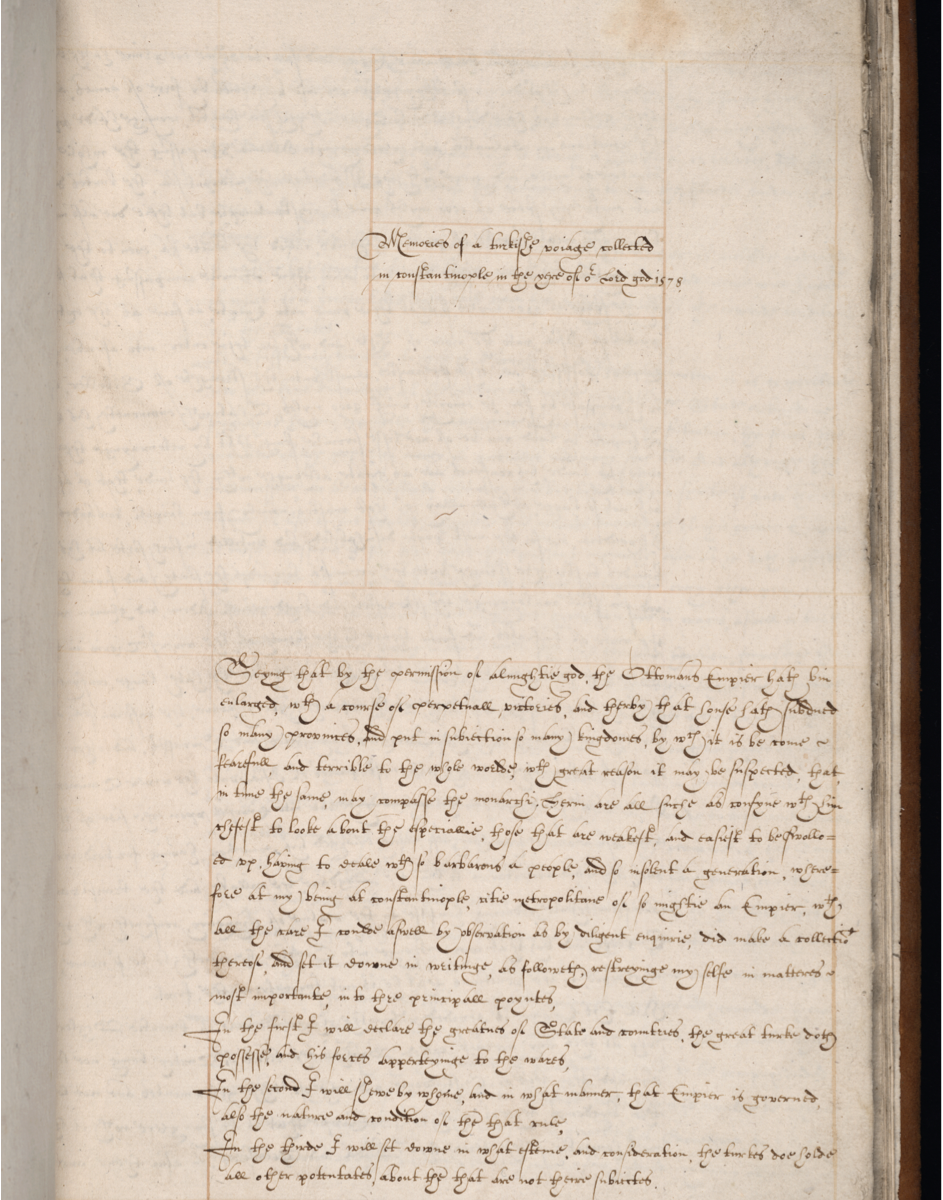

Kathleen Lea, Geoffrey Ashe and Leo Hicks all mention Sir Anthony Standen’s trip to Constantinople in articles, taking the account bearing his name on the title page at face value. Leo Hicks S.J. in The Embassy of Sir Anthony Standen, Recusant History, April 1963 states that Standen was in Constantinople in 1578 or before, citing the document now in the Beinecke Library: Relation of Sir Anthony Standen. Memories of a Turkish Voyage, collected in Constantinople in the year of our Lord God 1578. He remarks that Standen hadn’t disclosed in any of his writings why he went, but speculated that it was in connection with trade competition between the French, Florentines and English vying for Ottoman favour. Certainly, Elizabeth’s merchants were then in Constantinople, lobbying for privileges for the Levant Company. But the Relation of Sir Anthony Standen says little about tariffs.

To my eyes, it’s a clarion call by a military foe advertising unsuspected weaknesses in a long-time enemy, exhorting Christians to unify and take advantage of the naval victory at the Battle of Lepanto of 1572. The writing throbs with triumphalism, and a feral reappraisal of what had looked so mighty from afar, but really wasn’t.

Here’s a flavour. After stating that he made his observations personally in Constantinople, “having to deal with so barbarous a people and so insolent a generation,” the writer outlines Ottoman lands and client states, military forces and funding. Then he adds, “although these are necessary to be understood, yet are they but bodies without spirit if unto the other manner of life be not applied, wherefore this inward knowledge of this great Empire is most necessary.”

On this inward condition he’s scathing: “themselves do know and confess that although their Empire be great, and of so many Kingdoms, a great part thereof be weak, disinhibited and ruined…they also well know that their ancient valour and discipline is much decayed.”

Referring to the Battle of Lepanto, he asserts, “the Turks were of the opinion that the Christians durst not affront them, which now is contrary. Their minds being so overwhelmed with dread and doubt that they dare not so boldly presume upon the Christians. Confessing of their own free wills, as some of these have done to me, that their galleys in all respects are far inferior to the Christians, as well for the soldiers and men of combat, as also for mariners, galleotes, artillery, and other provisions pertaining to the sea.” He offers a plausible sociological analysis of why Ottoman crews don’t measure up to Europeans, rooted in gathered facts. Still, he marvels at their building of 170 galleys in six months to reconstitute their devastated navy, calling it “a feat incredible to those who saw it.” This doesn’t prove he was on the spot in 1573—it could have been hearsay—but it has the feeling of a witness account.

He sees the Ottomans as now rotten at the core, corruption bringing the least able to power. “…such manner of people are brought in, whose favours and greatness do grow by carnal affections, full of lechery and covetousness and above all replenished with arrogance and pride, which two vices are nourished in them by prosperity and good hap…All these are known truths to them, and hereupon will they not stick to say that in time these disorders will be an impediment to the conservation of all that they have gotten with so much blood…(but) to come to some other quality of their religion, I must say that few of them are there which hold the Mahomet religion to be good, which law is divided among them in opinions…yet in outward appearance the Turks are very strict observers thereof, for that few or none of them shall be seen to omit their ordinary prayers…” Transcription by Jacqueline Ly.

The accumulated weight of the writer’s verdict reflects an Ottoman government reeling from yesterday’s shocking drubbing, and looking inward. It is a distorted overview, more descriptive of the “sick old man of Europe” of the late nineteenth century than sixteenth-century Ottoman viability. This part of the text, particularly the frank exchanges the writer says he had with Turk officials, seems to have been written in the raw emotions of 1573-4, flush after Lepanto. But it is hard to place Anthony Standen out of Europe before 1577.

So who wrote these broiling words? Tune in next week for a candidate.