Dear friends and readers,

To welcome our new decade, I want to share another vignette from my enduring fascination with what made Elizabeth I an astute politician, one of the most successful European rulers of her time.

Confession: the drama of the near-failure and scramble to triumph of Elizabeth’s most cherished reform in 1560-62 excites me more than wondering how much heavy petting she allowed Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, in the same time frame.

The foundation of the Elizabethan regime’s strength was laid in the first two years. The religious settlement of 1559 created a somewhat moderate church, temporarily muting Protestant/Catholic clashes; while peace with Scotland and France resolved the wars that Elizabeth inherited.

Religious calm and external peace were two legs of the three-legged stool Elizabeth envisaged as essential to her ability to govern. Strengthening the debased currency, prerequisite to economic growth, was her top priority. Her first memo when she acceded, months before she was crowned, was a directive to reform English currency. She needed stability before embarking on disrupting that fundamental barter of goods and services for money.

The imperative to reform all English coinage, with no namby-pamby half-measures, was drilled into her by her financial advisor, Sir Thomas Gresham. He had served her Tudor predecessors and despaired, figuratively tearing his hair out, through multiple debasements to fund futile wars. His maxim was that “bad money chases out good.” What he meant was that if pure coins, where the value of the metal equals its nominal value, coexists in circulation with poor coins, where silver or gold is mixed with base metal, people will hoard or export the pure coins. The inevitable result is as if no good coins exist at all. Complete reform or nothing was required.

Elizabeth’s fledging government planned currency reform in secret. First, a comprehensive inventory of the extant coinage with three costed-out reform plans was delivered to Elizabeth in two months; then refiners were contracted.

Of course, recalling and re-minting every extant coin is impossible. The plan was that better coins (about 40%) would be re-mint to near pure silver or gold; and a “crying down” (markdown) of the rest to the value of its metal would account for the rest. The result would be “honest” currency for all denominations, acceptable anywhere.

If there is a platonic form of ambition, this is it!

Ironically, while the country was relaxing into a general quiet, re-coining preparations were at feverish intensity, with Elizabeth deeply engaged in the details. The impression of lull was so persuasive that a French diplomat at Elizabeth’s court reported that hers was the most frivolous court in the world. Nothing serious ever happened or was discussed, and he who elicited the loudest laughs was the most favoured.

He got a shock.

A rumor of debasement spread two days before the plan was ready, causing prices to rise. The government acted the next day.

On September 27, 1560, a comprehensive re-coining was announced. First, the marking down: some coins by 25%, the most debased by 60%. Bonuses with sequential date deadlines were offered for turning in poor coins, while the mint raced to release near-pure new coins. Dross from re-minting was sent for highway repair, while a debased coinage was established as Ireland’s currency. Poor Ireland. Already assigned leftovers! C. E. Challis in The Tudor Coinage (a history of all Tudor mintings and valuations) offers a thrilling account of how things nearly went wrong, and what a monumental task it was to try in the first place.

Elizabeth announced that sound currency was essential to combat rising prices, the scourge of inflation of the past decades. She admitted there would be short-term inconvenience. Urging patience, she wrote, “not much unlike to them, that being sick receive a medicine, and in the taking feel some bitterness, but yet thereby recover health and strength, and save their lives.”

It was her turn to get a shock.

Geography. Picture dusty couriers trying to ride the proclamations of new values to each town in the country ahead of rumors. Impossible. Then the assembling of sheriffs and local officials, their instructing each other on how to mark what coin.

Trust is everything in changing the value of coinage. The preceding eighty year of debasements had destroyed confidence. Counterfeiting by freelancers, financial crimes by venal officials, just plain mistakes, were possible. Dismaying reports of all three glitches flooded into London, forcing frantic improvisation.

The most controversial coin was the Edward VI silver shilling. One minting  showed the king with a short neck and round face. This was to be marked down by 25%. A later shilling showed him with a long neck and thin face, to be marked down about 60%. To the queen’s eyes, short-necked Edward was easy to distinguish from long-necked Edward; round face from thin face.

showed the king with a short neck and round face. This was to be marked down by 25%. A later shilling showed him with a long neck and thin face, to be marked down about 60%. To the queen’s eyes, short-necked Edward was easy to distinguish from long-necked Edward; round face from thin face.

I can imagine her outbursts when reports of wholesale mismarking came in.

“What!? All of Wells and Someset? Officials can’t tell round from lean? I’m sure they’re discerning enough at the butcher’s shops.”

The remedy was to make new punches featuring a portcullis for round-faced Edward and a greyhound for thin-faced Edward, to be stamped on the coins.

The remedy was to make new punches featuring a portcullis for round-faced Edward and a greyhound for thin-faced Edward, to be stamped on the coins.

Geography again: a scramble of little portcullis and greyhound galloped all over the country. Not enough of them and unevenly dispersed.

Reports came in that Wells and Somerset were mow mis-stamping portcullises and greyhounds, compounding their original errors. Were officials stricken by collective blindness, stupidity, were they venal criminals or political saboteurs? The success of re-coining hung in the balance. Some councillors urged prosecution. However, since “criminal intent” couldn’t be proven, the government sent reprimands and a supervisor

The Privy Council’s mild response here has always intrigued me, because it was an era of rigged trials and brutal punishments. Yet the legal concept of “intent” mattered to the young Elizabeth as her government raced to save currency reform from ruin. It was a vivid lesson for Elizabeth on the limits of control, one she rarely forgot.

When reform was complete by October 1562, the legal situation changed. Anyone spreading rumors of devaluation was sentenced to the pillory and three months in prison.

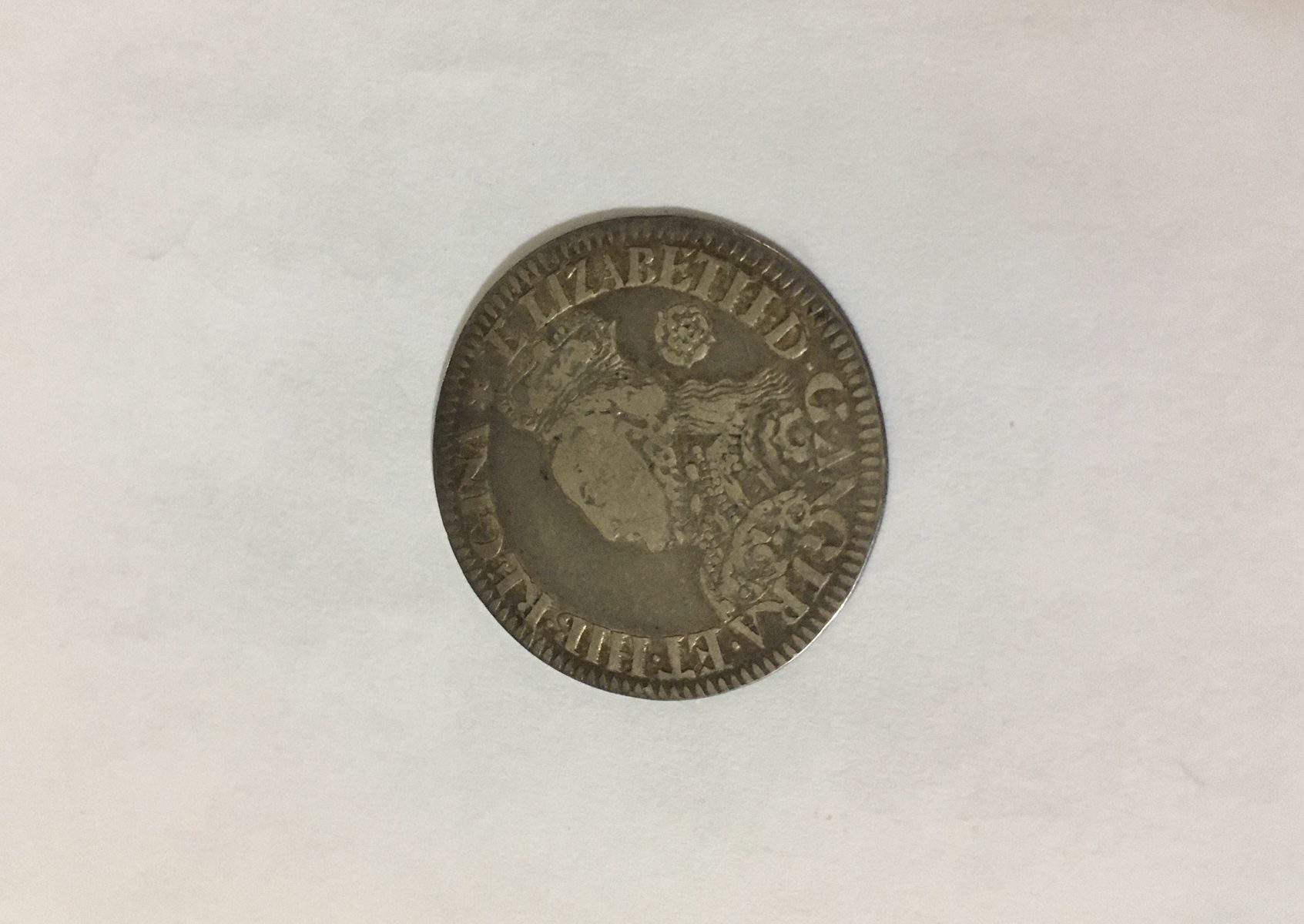

Currency reform was one of Elizabeth’s greatest achievements. Elizabethan coinage (my silver sixpence pictured here) was sought after at home and abroad throughout her reign. The English Exchequer even observed Elizabeth’s accession day as a holiday until late in the nineteenth century. Yet it was fragile: a few provincials almost derailed it.

Currency reform was one of Elizabeth’s greatest achievements. Elizabethan coinage (my silver sixpence pictured here) was sought after at home and abroad throughout her reign. The English Exchequer even observed Elizabeth’s accession day as a holiday until late in the nineteenth century. Yet it was fragile: a few provincials almost derailed it.