Dear friends: NEW FEATURE TO MY BLOG! Interviews with the authors presenting at the New York chapter of the Historical Novel Society, March 26th at the Jefferson Market Library.

Welcome Christina, thanks for visiting my blog!

You have had a long career as a musician and actress, in addition to being a writer. How is life for an aspiring actor/actress today different from what your Edwardian theater characters experienced?

Having spent my early life as a professional singer/actor, it is no wonder I chose the Victorian theatre to set my 4-book series HIS MAJESTY’S  THEATRE. Pouring through real and fictional theatrical accounts, I am especially fond of Charles Dicken’s NICHOLAS NICKELBY and Clarence Dane’s BROOM STAGES (rereleased as THEATRE ROYAL). Extensive research in London libraries completed my research. Actors who were not yet, or never would become, stars usually struggled to afford a dry roof and enough food to keep from starving. Theatrical boarding houses were few and far between, for good reason. If tickets didn’t sell, and/or a shady producer took off before paying his actors, midnight flits out back windows were commonplace. Even legitimate producers were allowed to withhold salaries if a performance was cancelled because of natural causes.

THEATRE. Pouring through real and fictional theatrical accounts, I am especially fond of Charles Dicken’s NICHOLAS NICKELBY and Clarence Dane’s BROOM STAGES (rereleased as THEATRE ROYAL). Extensive research in London libraries completed my research. Actors who were not yet, or never would become, stars usually struggled to afford a dry roof and enough food to keep from starving. Theatrical boarding houses were few and far between, for good reason. If tickets didn’t sell, and/or a shady producer took off before paying his actors, midnight flits out back windows were commonplace. Even legitimate producers were allowed to withhold salaries if a performance was cancelled because of natural causes.

At least jobs for actors were plentiful. Experience was seldom a prerequisite for hiring. Actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree was the first to teach acting technique. In 1904, his classed evolved into the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Most actors learned on-the-job. Tree built Her Majesty’s Theatre in 1987. When Edward VII was crowned in 1901, the theatre name was changed to His Majesty’s.

Most actors were expected to learn their roles from sides, (sheets with only their own lines on the page). They provided their own costumes, wigs, and makeup. There are accounts of dancing girls spending most of their hard-earned wages replacing torn stockings.

In small road companies, the actors were also the backstage crew, setting up their stage, rigging, lights, making and mending costumes, and roaming each new town, passing out tear sheets and selling tickets. A newly hired actor could be expected to learn several long roles almost instantly, rehearse night-and-day, and still have enough energy to project his/her voice over a rowdy audience. If a small company played a town for 8 days, they need to perform 8 different plays. Old actors could seldom stand these rigors, so young actors drew overlarge wrinkles onto smooth brows, powered dark hair to make it gray, walked bent over, and tried to look old.

The few star actors and actor-managers like Henry Irving, and Herman Beerbohm Tree made vast salaries, built their own theatres, and treated their actors fairly. They also took their companies on tours of the world.

Many well paid “tragic actors” took time from the legitimate theatre to play Pantomimes. These elaborately silly holiday children’s shows rehearsed for 3-4 weeks, opened on Boxing Day (December 26th) and played for several weeks. Rehearsals were not paid, but actors could still earn more in a short Pantomime season than an entire year playing small roles for Henry Irving.

Learning all this quaint information made me shake my head. Being an actor is 2019 is very similar. The major difference is that now, there is less work for actors.

I was lucky to get a union card at the age of 7. Actors Equity Association demands producers pay a bond before a show goes into production. This insures that actors will be paid and brought home, even if a show closes out of town. Rehearsal and performance hours are still long, but reasonable. Even working in summer stock, when one show is playing 8-9 performances a week, and two more shows are rehearsing during offstage hours, the actors and crew are guaranteed 11 hours off after an evening curtain falls and rehearsal can begin the next day. Contracts vary according to the budget of the theatre, but breaks for meals, warm dressing rooms in winter, and other basic necessities are guaranteed.

Non-union theatres still do whatever they want. The only nonunion gig I played was Jenny Lind in BARNUM on a cruise ship. There were no unions on the high seas. The play alternated nights with a Los Vegas type review called SEA LEGS. I was horrified when a new SEA LEGS number was put into that show and the dancers were rehearsed all night, after the BARNUM curtain came down. They were allowed a couple hours sleep before the next BARNUM matinee. Since that is a circus show, with some dancers swinging on ropes over the audience, it was amazing no one got hurt.

In 2019, every theatre performer wants to be on Broadway. The work is hard, but salaries and perks are high. Walking through Times Square, pedestrians are accosted by attractive young people costumed from a current show, handing out fliers. These actors are never in Broadway shows, but may be in Off Broadway shows playing just around the corner.

Much like 19th century Pantomime stars, modern TV/film stars performing on Broadway take huge cuts in their usual salaries. One female star told an interviewer she was paying her nanny more that she was taking home in her pay envelope.

The summer stock season of 1988, I was cast in THE WOMEN. The show is about the scandal of divorce in the 1930s. Since regional theatre producers can ask actors to provide their own clothes for contemporary plays, they decided to set the play in 1988. When the director arrived, reminded them there was no scandal of divorce in 1988 and the play would be nonsense, most contemporary clothes brought by the actors didn’t work. Anticipating the problem, I brought clothes that worked for both periods. The rest of the cast scrambled, sent home for other clothes and went shopping.

We were always paid on a Friday, and the last show of the week was on Sunday. Before the very last Sunday show, we had not been paid. One of our stars, Julie Newmar, (best remembered as Cat Woman), refused to go on until we were all paid. Thanks to Julie and the Equity bond, we were paid and flown home to New York.

Reference: Jackson, Russell VICTORIAN THEATRE – A & C Black, London, 1989

I have always admired your versatility in casting your material in first or third person, epic novel, novellas or play. How do you get the perspective to rework material you’re so close to?

In his advice to authors, the great Ken Follett writes that we must expect to write 500 pages and rewrite 500 pages. Both my first published novel, ONE MAN’S MUSIC, set from 1960-1978, and my 4-book historical novel series, HIS MAJESTY’S THEATRE, 1885-1904, have been rewritten more times than I can remember.

In my first career, I was as an opera singer. I performed in European opera houses and returned home to NYC expecting to become a star. It never happened. In the middle of a ten-week run at Radio City Music Hall, I auditioned for a Broadway chorus. ON THE TWENTIETH CENTURY was going on a six-month tour starring Rock Hudson and Imogene Cocoa. I already had an idyllic summer stock job lined up. I was going to earn little, but be a star in the Maine woods for 3 delicious months. When I got the long, lucrative, prestigious, boring Broadway chorus job, I cried.

A month into the tedious run, I sat backstage, listened to the stars sing their solos, and hoped the actress I understudied would catch cold. Bored and discouraged, a story came to me about artistic dreams that might never come true. ONE MAN’S MUSIC had lust and longing, girl bonding, hot sex with the man of my dreams, and especially music. Writing was such a joy I got miffed every time I had to stop and go onstage. I wrote it as a short story, a song cycle and a screenplay. The screenplay was a competition finalist and requested by a production company. Sadly, it has not been produced.

Later, I extended it into a full-length novel in the third person. My literary agent loved it, but could not sell it. After a couple of years of publisher rejections, she suggested I rewrite in the first person. By that time, my battered writer’s ego was game for anything. Ken Follet also says that we must, “murder our darlings.” Telling the story in the first parson meant cutting out any scene my young soprano did not experience or hear about. Using the device of her overhearing grownup conversations, I was able to keep most of the story intact. Scenes she could not possibly know about had to be deleted.

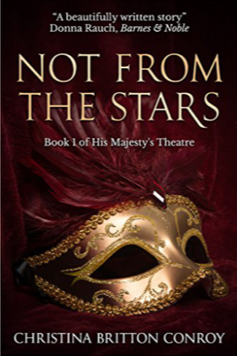

HIS MAJESTY’S THEATRE was originally a single 600-page volume. Jeremy,  my Victorian actor/manager narrated the story bits he was in. The other plot lines were in the third person. Jeremy speaks in a theatrical voice, never uses contractions, (can’t for cannot), and enjoys overlong words. When the book series was accepted by a publisher, some of Jeremy’s pompous language survived and needed to be stripped out. I had him reading the newly published WIZARD of OZ and thinking that, “…it would translate brilliantly to the stage.” My clever editor changed that line to, “…it would make a good play.”

my Victorian actor/manager narrated the story bits he was in. The other plot lines were in the third person. Jeremy speaks in a theatrical voice, never uses contractions, (can’t for cannot), and enjoys overlong words. When the book series was accepted by a publisher, some of Jeremy’s pompous language survived and needed to be stripped out. I had him reading the newly published WIZARD of OZ and thinking that, “…it would translate brilliantly to the stage.” My clever editor changed that line to, “…it would make a good play.”

In my first screenwriting class, I condensed all 600 pages into a 120-page screenplay and was told it was utter rubbish. I wept and swore I would never try that again. Fortunately, I was also told not to despair. Learning that screenplays of long books strip out and condense plotlines and characters, I eventually wrote several screen adaptations, emphasizing different subplots within my long novel.