Dear friends and readers, here’s my continuation on how Elizabeth and her councillors managed each other during political turmoil in the 1580s and 90s. I have drawn my material from Barbara Freedman’s superb article Protest, Plague and Plays: Rereading the “Documents of Control.” English Literary Renaissance, Vol. 26 # 1, Winter 1996. University of Chicago Press.

As I wrote in the first blog, Freedman compares data on Elizabethan theatre closings due to plague, plague bill statistics, social disorder events and her own research into Privy Council minutes and proclamations. A fascinating and nuanced picture emerges. When it came to Catholic dissent, Elizabeth preferred severe punishment of individual perpetrators over collective oppression, while her chief councillors advocated broad repression. Elizabeth prevailed on religion. But social disorder got more complicated. There were mass protests over food shortages, job shortages, corruption.

In Elizabeth, the Forgotten Years, John Guy describes an Elizabeth withdrawing into herself, unable to come to terms with the fact that, because of a war she never wanted to fight, her foundational reforms were in danger of unravelling. Freedman sheds light on tricks Privy Councillors played on her to get through the worst of times.

In Elizabeth, the Forgotten Years, John Guy describes an Elizabeth withdrawing into herself, unable to come to terms with the fact that, because of a war she never wanted to fight, her foundational reforms were in danger of unravelling. Freedman sheds light on tricks Privy Councillors played on her to get through the worst of times.

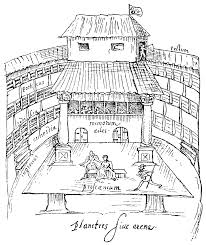

There was only one legal way for people to assemble: at the open-air or closed theatres and bear-baiting pits. Some entertainment spaces were near the granaries, a natural staging place for protests, brawls and riots. Some theatres could accommodate 3,000 people.

And here is where Elizabeth’s longstanding preference for punishing individual perpetrators instead of collective repression collided with reality. She believed that her subjects should be free to enjoy plays, blood sports and games. Individual rioters should be imprisoned, their leaders tried and quartered for treason. When city authorities begged her to close theatres on the Thames south bank during a riot, she refused. The plays must go on! She was more inclined to order martial law and send in provost-marshals.

There were two problems with this. First, there were SO MANY disaffected individuals to punish that oppression would spawn more protests; prison break-ins did occur. In addition, the government was in a conundrum. Despite its harshness and the misery of the times, it was responsive enough to make protesting worthwhile. Food riots and theft of ship cargoes led to increased grain imports, food consumption by the rich was ordered rationed with more collections for the poor. The famous Poor Laws were enacted in 1598. There was a potential upside to protests.

The second problem with keeping the theatres open and declaring martial law was that local officials didn’t want it. They might have liked muscular Crown support, but had to pay for it. That raised the loathsome prospect of increasing local taxes.

What to do?

Stay tuned…